Questions Concerning Wind Power?

- What is a wind turbine?

A wind turbine is an engineered structure that converts energy in wind (moving air) into electricity.

Most modern wind turbines look like giant fans with three blades. This fan-like structure is called a “rotor”. The blades on the rotor have a design similar to airplane wings. When the wind blows into them, the air moves around each blade to create a force called “lift.” On an airplane wing, the lift force points upward, raising the wing and thus lifting the aircraft into the air. On a wind turbine rotor, the lift force points in a circular, clockwise direction, which causes the rotor to rotate. Rotors typically rotate at speeds ranging from 8 to 20 rotations per minute (rpm) when the wind is blowing at the turbine’s “rated wind speed,” which is the wind speed for which the manufacturer has designed the turbine to operate optimally.

At the center of the rotor is a shaft, which is a long spinning cylinder, similar to the axle on a wheel. The rotor is coupled to the shaft so that the shaft spins at the same speed as the rotor. The shaft extends behind the rotor where it connects to the electrical generator. The generator converts the mechanical energy of the shaft to electrical energy (electricity). Electricity leaves the generator through power lines that deliver electricity to the local electrical distribution or transmission system.

2. How is a wind turbine different from a windmill?

Wind turbines and windmills have a lot in common. Both have a rotor and central shaft. However, windmills are designed to produce mechanical energy instead of electricity. Instead of connecting the central shaft to a generator, the spinning shaft itself is the desired output. Many useful machines can be driven from a spinning shaft, including water pumps, flour and corn mills, and cutting tools. In addition, windmills are usually much smaller in size and simpler in design than are turbines, and they have been around for well over a thousand years. Instead of the three large blades of a modern wind turbine, they may have many smaller blades. Also, modern wind turbine blades are made from advanced materials, such as carbon fiber and polyester reinforced with plexiglass. Windmills are made from wood, cloth, and other natural materials.

3. What is the difference between wind energy and wind power?

“Energy” is a quantity of something. That “something” is the capacity to do work. “Work” is the application of force on a body so that the body moves in the direction of the force.[1] In this sense, energy is like distance, which is the amount of space between two points. We count energy in units such as Calorie (energy content of food), Btu (thermal energy), joule (chemical and mechanical energy), and kilowatt-hour (electrical energy).

“Power” is like speed. Speed is the rate at which we cover distance. Power is the rate at which we use or transfer energy. We count speed as distance per unit of time; for example, miles per hour (mph). Similarly, we count power as energy per unit of time; for example, Calories per hour (Cal/hr), Btu per second (Btu/s), and joule per second (J/s). This last unit, J/s, has a special name: watt (W). Electrical power is often given in units of kilowatt (kW), which is thousands of watts. In reference to power plants, power is often given in megawatts (MW), which is millions of watts (or thousands of kilowatts).

Power always refers to how fast we are generating or using energy. Many appliances are rated in terms of their power consumption. For example, a microwave oven may operate at a power level of 1500 watts (1.5 kW). Suppose we operate the oven for one hour. How much energy would we use? To find the amount of energy, multiply 1.5 kilowatt by 1 hour to obtain 1.5 kilowatt-hour (1.5 kWh) of electrical energy.

The average American home uses around 30 kWh of electrical energy each day (30 kWh/day). Assuming a constant rate of electricity use, this home consumes electrical energy at the rate of 30 kWh/24 h = 1.25 kW. Suppose a small town has 100 such homes. To provide these homes with electric power, we would need a power plant that could generate electricity at the rate of (1.25 kW/home) X (100 homes) = 125 kW. In reality, we would need more capacity, since household electricity usage varies over the course of the day, and the plant would need to be able to meet the peak demand during the day.

[1] Although energy comes in many forms, it must be convertible into the mechanical application of a force to a body (which may be as large as a car or tiny as an electron) so that the body moves in the direction of the force. Otherwise, it is not energy.

4. What happens if the wind doesn’t blow at the wind turbine’s rated wind speed?

Wind turbines only generate electric power when the wind speed exceeds a lower limit, the “cut-in speed” and is less than the upper limit, the “cut-out speed.” A turbine designed for a place with low-to-moderate wind speeds might have a cut-in speed of 7 mph, rated speed of 17 mph, and cut-out speed of 55 mph.

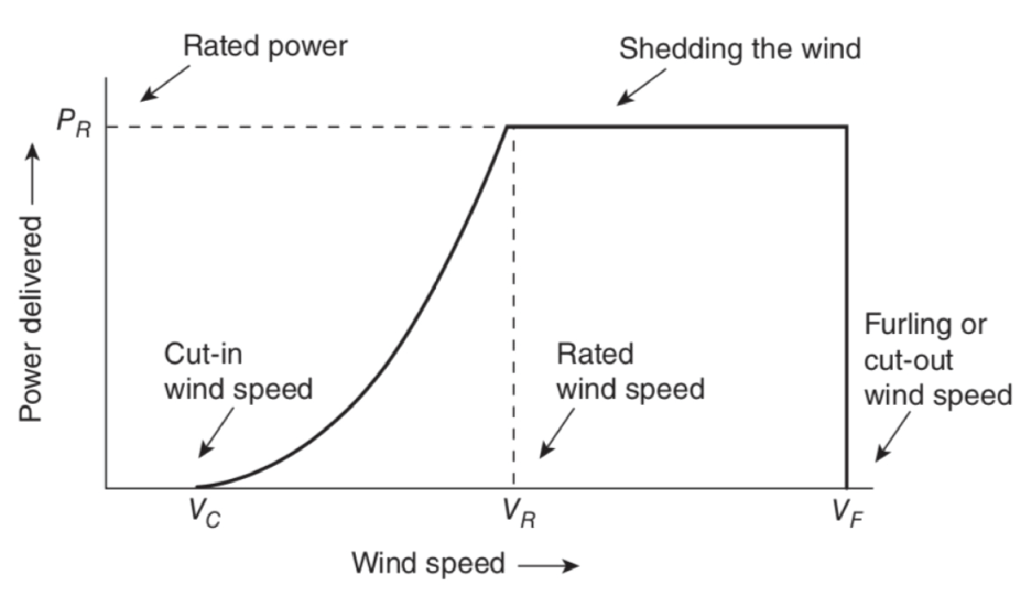

The diagram shows the general features of a wind power curve.

When the wind speed dips below the cut-in speed, the turbine produces no power. Above the cut-in speed, the rotor’s speed of rotation rises exponentially as more wind energy is captured by the blades. The rotor speed reaches a maximum at the rated wind speed, and beyond that the speed of rotation and power delivered remains constant, even as the wind speed continues to increase. Once the wind speed reaches the cut-out speed, the turbine shuts down to prevent excessive wear and damage.

5. How much electricity will a wind turbine produce in one year?

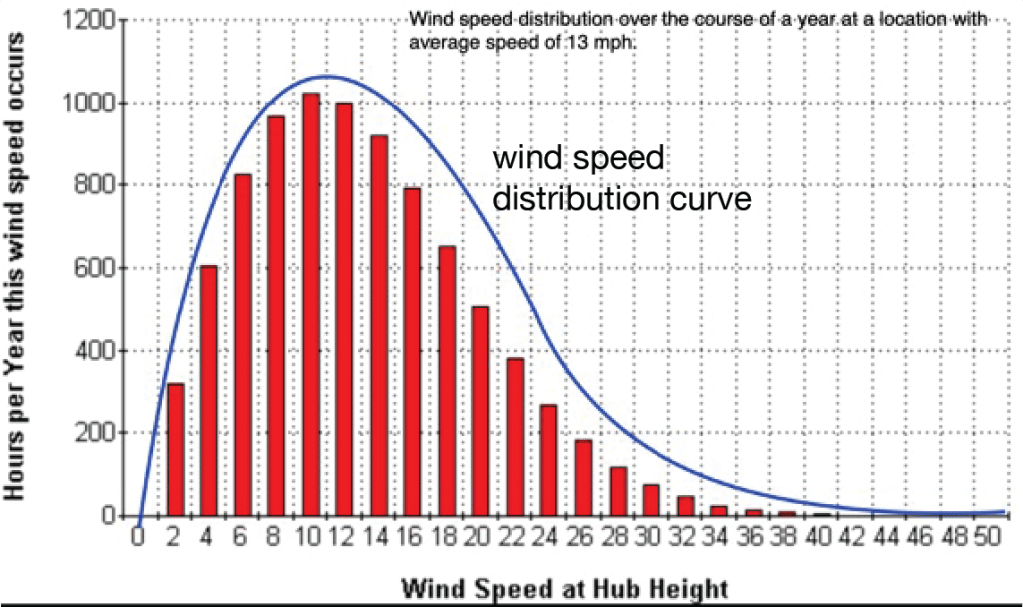

The electric power output potential from a turbine depends on the distribution of wind speeds at the location where the turbine is sited. A wind assessment is performed at the site to determine the hour-by-hour wind speed over the course of a year (8760 hours). The wind speeds are displayed on a graph like the one at right with the red bars. The horizontal axis shows the wind speed, which ranges from 0 to 50 mph. The vertical axis shows the number of hours during which the wind was observed to blow at each wind speed shown on the horizontal axis over the course of the year. Connecting the peaks of each bar reveals the wind speed distribution curve. In this example, the average wind speed is 13 mph.

According to physics, the power in wind increases with the cube of the wind speed (in other words, a doubling of the wind speed yields an eight-fold increase in power). For this reason, even a slight rightward shift in the wind speed distribution curve, increasing the average speed, translates into a much larger increase in power and comparably large increase in electric power output. Not surprisingly, the most desirable locations for siting wind turbines are places with high average wind speed.

The amount of electrical energy a wind turbine generates in one year depends on the wind speed distribution and the turbines’s power output at each wind speed. Multiplying the power output (MW) at each speed by the number of hours in one year that the wind blows at that speed (Hours/yr) gives the annual energy generated by the turbine at each speed (MWh/yr).

Consider the graph.

The lightly shaded bars, like the red bars in the graph above, show the wind speed distribution in hours per year (Hours/yr). The darker bars show the amount of energy generated per year (MWh/yr) at each wind speed.

Now here’s the key point:

Note that most of the turbine’s electricity output occurs at high wind speeds. Although most of the time the wind blows at 8 m/s (18 mph) or less, most of the energy output occurs when the wind speed is greater than 9 m/s. At low speeds, little energy is generated because of the lack of wind. At very high speeds, little energy is generated because the wind doesn’t blow for very many hours at such high speeds.

The takeaway here is the following:

- Wind speed varies greatly over time.

- For many hours in a year, the wind speed falls below the threshold required for the turbine to generate electricity in significant quantity, or even to generate electricity at all.

- Wind turbines produce the greatest quantity of electrical energy during the relatively short periods of time when the wind speed is high.

- Because of points 1-3, energy output from wind turbines varies greatly over time; for not insignificant amounts of time, the output is zero.

6. Why are wind turbines so large?

Average wind speeds increase with height above the ground. This is because buildings, terrain, and vegetation on the ground exert a drag on the wind, slowing it down near the surface. Since power in the wind varies with the cube of the wind speed, developers have a great incentive to build tall turbines that can reach into the faster winds high above the ground.

Wind power output increases with the square of the rotor’s diameter. Double the diameter and the power output quadruples. As a result, developers have a strong incentive to build turbines with very big rotors. Rotor blades have become so long that transporting them to the site can present significant logistical challenges.

7. How efficient are wind turbines?

Under the laws of physics, wind turbines have a theoretical maximum efficiency of 59 percent. In other words, no more than 59 percent of the energy in wind can be captured by the rotor. The air must retain some residual energy so that it can move away from the turbine after flowing across the blades. If the turbine were 100 percent efficient, the air would be completely still on the backside of the rotor; this still air would form a wall of air molecules blocking the incoming air. Well-designed modern turbines have attained efficiencies ranging from 45 to 50 percent.

8. Can wind turbines alone meet our residential electricity needs?

The output of a wind turbine is limited by its “capacity factor.” The capacity factor (CF) is the fraction of time in a year when the turbine generates power at its rated output. It can be calculated as the number of hours when the wind speed ranges between the turbine’s rated wind speed and the cut-out speed divided by the total number of hours in a year (8,760). The capacity factor increases in rough proportion with the average wind speed. Modern turbines have capacity factors ranging from about 0.21 in regions with light winds to 0.52 in regions with strong winds, with a national average of about 0.35.

Suppose a wind turbine has a rated power of 5 MW (5,000 kW) and a capacity factor of 0.35 at a particular location. Over the course of one year (8,760 hours), this turbine could be expected to generate a total of (5,000 kW) X 0.35 X (8,760 hours/year) = 15,330,000 kWh of electrical energy. Assuming that electricity use is constant throughout the day and year (again, a significant oversimplification but useful for quick, rough estimates), the average daily electricity production is 15,330,000/365 = 42,000 kWh/day. Since the average home uses around 30 kWh of electrical energy each day, this turbine could, in theory, meet the needs of 42,000/30 = 1,400 homes.

Here is where the difference between power output and total energy over a period of time becomes extremely important. Wind turbines produce electric power only when the wind blows at speeds greater than the cut-in speed and less than the cut-out speed. No matter how high the average wind speed at a location, there will be many hours during the year when the wind is calm or below the cut-in speed. This means that during a significant period of time, no electric power is produced. Worse, the exact times when the power output is zero cannot be known with certainty in advance but are subject to local weather variability. Although a wind turbine may, in theory, generate sufficient energy over the course of a year to meet the needs of many homes, in practice it will produce more energy than needed at some times and less energy, or no energy at all, at other times.

There are several ways to address the problem of intermittency of power output. One is to store electrical energy in batteries or other storage system at times when the turbine produces more energy than needed. When the turbine’s power output falls below the demand for electricity, the deficit can be covered by discharging the batteries.

Second, supplement the power from wind with power plants that can be switched on quickly when more energy is needed and switched off when backup electricity is no longer needed. Hydroelectric plants often work well in this capacity, though usually fossil fuel plants that run on natural gas fulfill this role.

Third, build many more turbines than a location requires to meet the average annual energy need, and spread the turbines out over a very wide area to increase the chance that wind will be blowing at some of the sites. While this may sound good in theory, in practice no amount of wind turbines will produce electricity on calm days, which tend to occur during extremes of humid heat and cold, when the demand for electric power is greatest. In addition, a large and complex system of transmission lines and associated hardware would be needed to interconnect all the turbines.

Finally, wind turbines, strategically placed in high-wind locations removed from communities where people live, can be complemented by large, central power plants that provide a constant level of power output throughout the year. Nuclear power plants play this role exceptionally well, as do many hydroelectric plants. For the occasional periods when the demand for electricity is very high, the additional margin of power can be supplied from hydroelectric, solar, or fossil fuel plants equipped with the latest pollution control technologies.

9. Do wind turbines endanger the health and safety of people and animals?

Earlier it was noted that the rotors of large wind turbines turn at speeds of 8-20 rotations per minute. While this seems slow—and indeed we often see images of blades turning gently and gracefully—the outer tips of the blades are racing through the air at speeds ranging from 100 to 200 miles per hour. The reason they move so fast is that the blade tips must keep up with the slower-moving blade parts near the central hub; the longer the blade, the faster the speed of the tip at a given rotational speed of the rotor.

These fast-moving blades not only pulverize anything that comes into their path, they also create significant turbulence in the air, as well as a suction effect, like that on the suction side of a fan. Bats and birds are especially susceptible to collisions with blades, as well as injury, or death, from merely happening to be in the vicinity of the turbine. Place a thin piece of paper in back or front of a household box fan and watch the effect. Now replace the paper with a bird and the fan with a giant wind turbine.

Wind turbines also generate noise, both from the moving mechanical parts and from the air being whipped up by the huge rotating blades. Many people in the vicinity of a turbine find the noise annoying, and the continuous thrumming, especially at low frequencies, can have detrimental longterm health effects.

In addition, the passage of sunlight through the rotor as it sweeps through the air creates a flickering effect. Again, many people find this flickering annoying and a source of stress.

Moreover, by extracting energy from wind, wind turbines change the speed and direction of winds in their vicinity. While the effects may be negligible for a small number of turbines, the change in regional air circulation resulting from dozens or hundreds of turbines clustered into wind farms is not be trivial. The long-term effects of changing air flow patterns in this manner are simply not known.

Finally, the sheer size of modern wind turbines means that they loom large over their landscapes. To capture the faster wind high above, giant towers raise the hubs as high as 350 ft or more above the ground. The total height of the turbine, ground to tip, when a blade points vertically upward is greater than the length of two football fields. Such massive edifices will be visible across the surrounding region, changing rural vistas and environmental aesthetics in ways many people may not find pleasing. They also require large amounts of concrete and other materials, as well as foundations sunk deep into the earth, to ensure structural integrity and stability. The disruption to soil and local geology cannot be ignored.

10. What is the verdict on wind turbines as an energy source?

All power plants have their pluses and minuses; wind turbines are no exception. They generate electricity without polluting the local air or adding to greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. While they are large in size with a presence some may find ugly and intimidating, many people would be at least as uncomfortable having a fossil fuel or nuclear plant imposed on their communities. Finally, the price of electricity from wind turbines is cheap in comparison with other power plants (even without government subsidies). There is no fuel to buy, and maintenance is relatively inexpensive. When the wind blows, the cost of producing electricity is, practically, zero.

On the other hand, power output from wind turbines is intermittent. At times of little or no wind, no electricity is produced. Worse, wind tends to be calm at times of greatest demand for electricity, and predicting wind speeds is subject to limitations inherent in forecasting the weather. With huge rotating mechanical parts whipping air at high speeds, wind turbines endanger the life of any animal or person that comes into proximity, while posing risks to the health of those who experience the noise and visual impacts on a daily basis. And as with any construction project, erecting large turbines disrupts the natural environment. Finally, wind turbines require various natural resources, such as copper and rare earth metals, that are expensive, found in limited quantities, and obtained or processed outside the US. Maintaining a stable, reliable supply of these resources will always entail risk, especially when they come from unfriendly countries or regions that do not respect basic human rights.

As with the siting of any public infrastructure, the voices of the people in the communities who will live near the structure and bear the burdens of hosting it should be heard. Politicians far removed physically from the site should not have the final say, nor should developers and others with a financial stake in the outcome. And by no means should a community be bullied into accepting such projects with threats of financial penalty or withdrawal of a benefit.

In the end, the local citizens should have the final word, but only after the project has been objectively presented to them, the costs and benefits fully revealed, and ample time allowed for study and deliberation.

Steven W. Collins, PhD, PE (NY WA)

Van Hornesville, NY

The views expressed herein are those of the author, and he alone takes responsibility for the content.